Monart Glass

Frank Andrews 2002

Edited by Mary Houston-Lambert

Monart Glass - Introduction

Monart Glass was manufactured from about 1922 until c.1961 at Moncrieff’s North British Glassworks, Perth, Scotland. It was developed by Salvador Ysart, a master glassmaker originally from Barcelona, Spain, and his four sons: Paul, Augustine, Vincent and Antoine. The production really began in 1924, but was sporadic and based on orders received. During World War II and shortly after, 1939-1947, production was limited to the work the family did in their spare time. For the most part only the Ysart family worked on the glass, although the grinding and polishing was done by Frank Stewart. Salvador’s oldest son, Paul, developed an interest in paperweights in the early thirties and was to go on to become one of the greatest paperweight artists of the twentieth century. Salvador and his two sons, Vincent and Augustine, left Moncrieff’s in 1946 and set up their own glassworks, Ysart Brothers Glass, producing glass under the name ‘Vasart’. Paul remained at Moncrieff’s until 1963. Salvador’s youngest son, Antoine, had died in 1942 as a result of an accident.

|

Two catalogues of Monart glass were produced by Moncrieff’s, one with four pages under the “Monart Ware” label and the second with 11 pages under the “Monart Glass label”. On this website, are images of the “Monart Ware” catalogue and the “Monart Glass” catalogue, which have been recreated with colour photographs replacing the original black and whites, where available. The site also shows additional pages with variations in shapes, un-catalogued shapes, lighting, paperweights, and the colours used. The criteria for adding ‘new’ shapes is quite rigorous, and is based on ‘Special’ labels, documented pieces, and consistency in colours and technique.

The style of glassware developed by the Ysarts was born in the ‘Nancy’ art glass movement that was started by Emile Gallé around 1901. Salvador Ysart had migrated to Lyons, France, after learning his trade in Barcelona, Spain - presumably eager to be involved in this new wave of glass creation. Monart glass has often been compared to the style of the Schneider brothers, with whom Salvador worked briefly before the First World War. But this does not bear up to scrutiny as Schneider developed their Monart-related style after World War I, according to their catalogues. However, this was a time of experiment and new ideas would travel quickly in the glassmaking community throughout Europe.

Another important aspect of the early period at Moncrieff’s was the use of millefiori canes in decorating very early vases and objects. This development by Salvador was to lead to Paul Ysart’s interest in paperweights and, subsequently the entire Scottish paperweight industry, which developed in the 1960’s and 1970’s. While it is known that Paul Ysart started to take an interest in paperweights in the early 1930’s, the origins of Salvador’s expertise in this area remains unclear and still the subject of ongoing research by collectors.

It is fair to say that this Spanish family has had a dramatic impact on the production of glass in Scotland, and indeed world-wide. Oddly, the glass was largely unrecognised until the book Ysart Glass was published in 1990. During the 1930’s, Monart glass had been sold in prestigious outlets, such as Liberty’s in London and Australia, and in the United States; it was quite expensive. There are two reasons for its slow recognition in the glass collecting community: firstly, the glass was rarely signed, and secondly, it was made in relatively small quantities. Also, it did not help that it was created with a fairly coarse glass and that pieces were frequently seen with annealing cracks. Even as it began to emerge on the British collecting scene in the 1980’s, it was still largely side-lined by the major auction houses in London. It was the influence of one collector, Michael Parkington, that finally gave it status. To commemorate his impact, I include a small chapter here.

Michael Parkington

Michael Parkington was a prolific collector of British glass from earliest days to modern times. His career was also notable: a lawyer by profession, he had moved to South Africa to practise law.

|

|

|

Michael: The caption was one of Michael Parkingtons favourite statements on collecting. |

There he successfully defended Nelson Mandela in his first trial by the South African government. After the trial, he was warned that he was to be dealt with by the Secret Service, so he immediately left the country and returned to the UK, where he became a leading marine insurance lawyer and a noted collector of silver. The insurance companies frustrated him by insisting that most of his collection be kept in vaults, and this led him to abandon the silver and start collecting glass.

I developed a pleasant friendship with Michael and learnt more about glass in those few years than I had ever imagined possible. I suspect Michael took pity on my ignorance of glass history and decided to put that right - he was quite successful. Mostly we shared a passion for glass in the drawing room, with just a few pieces to discuss, argue about, or simply enjoy.

For me, it was a magical experience to be in his dining room, where the walls, floor and a huge mahogany dining table were solidly packed with glass. Throughout the rest of the large Kensington apartment no glass was in sight, as his wife Peggy refused to allow it to spread. However, almost every cupboard in the apartment was also packed with glass. A small office contained his Varnish glass collection together with pieces under current study. Another room served as the laundry with a dedicated glass cleaning section. A walk-in cupboard contained his research material – the only door I was never invited through. Other parts of his collection were on loan to museums, and his rejects were usually sold at Asprey’s in Bond Street.

In the dining room, I could see and handle some of the most unique and rare pieces of English glass: a selection of “Silveria” and some of the best carved Cameo ever to have come out of the UK. Over those years I was delighted to help him put together an unrivalled collection of Monart and Vasart glass. Michael was fastidious about not collecting damaged glass, and he moaned about my newsletter remarks saying that damaged Ysart Glass was collectable. But as he became more and more in love with Monart he finally bought a damaged piece from me. For the next month I got phone calls complaining that I had corrupted his entire collection; however, he kept that piece and added two more damaged pieces later, one of which was completely covered in minute annealing cracks. He actually found it fascinating for its ‘unusual imperfection’.

A large part of “The Parkington Collection” was sold at Christie’s South Kensington in a two-part sale. The first part was held on 16th and 17th October 1997, containing over 230 pieces of Ysart glass in 109 lots. The second part was held on 8th April 1998, containing over 260 pieces of Ysart glass in 137 lots. The sales included Monart, Vasart, Strathearn, and Paul Ysart paperweights. Some of the pieces that had been perfect were mentioned as damaged. Also, there are a few incorrect attributions in the catalogue: for example, a Vasart bowl in lot 460. But the majority were correctly described. I presume that the pieces not sold at auction had gone directly to museums. I received one piece from his widow: a DH vase lamp, shown in the lighting catalogue as FL16, for which I had made Michael a lamp fitting.

John Moncrieff Ltd

The company was set up in Perth by John Moncrieff (Senior) in 1865 as the North British Glassworks, South Street, Perth. During the 1880’s it was re-located to St Catherine’s Road where all of the Monart glass was later produced. In 1905 it became a limited company: “John Moncrieff Ltd” owned by John Moncrieff’s son, John Moncrieff (Junior). The main output of Moncrieff’s was glass tubing, heat resistant glass for steam gauges, using a borosilicate glass with the trade names ‘Perth’ and ‘Unific’ - a forerunner of Pyrex. Other pieces, such as the shooting targets shown here, were made in different colours and filled with feathers. A lot of glass fragments must have been left behind after use!

In 1928, Moncrieff’s introduced a range of bottle-making machinery under the trade name “Monish”; this was later marketed by a separate company, the Monish Glass Machine Company. They had briefly produced hand-blown bottles but did not find their facilities ideal for this. The firm was ever innovative and had employed chemists and scientists to develop new products and technology. Originally they had used a conventional skittle pot furnace but later developed an improved tank furnace which increased production speeds.

|

| Moncrieff Target Ball |

For the war effort, Moncrieff’s extended to laboratory glassware which was produced under the trade name ‘Monax’, another variety of borosilicate glass that they had developed. In the 1990’s Moncrieff’s were renamed ‘Monax’. More details of all the company changes and some employees are given on the companies page.

| Moncrieff Works layout c.1950- |

|---|

|

The sketch shows factory top floor which remained virtually unchanged for about fifty years. The main tanks shown are the borosilicate tanks and they were alternated every 6-7 years, according to the lifespan of the furnace. The old tube run is not shown as it disappeared a long time before.

Two of the old employees who worked with the Ysarts confirm that the location of the Ysart working area is correct, and that no-one except the Ysarts, was allowed into it. A small stock of colours was kept there, together with some tools.

A minor detail in the whole scheme of things, the soda tank showing next to Paul Ysart's working area does point to the use of soda as a base glass.

John Moncrieff (Junior) married Isobel Dunlop and it was her interest in the glass being made by Salvador that took it from being a glassblower’s “friggers” to a comprehensive product line. Isobel actively marketed the glass, which was sold by Liberty’s of London and a few other prestige stores. The British Linen bank provided additional financing to Moncrieff’s in 1933, at which time John Moncrieff was forced to resign as Chairman and sell his shares. Isobel had no further influence on the design of Monart, and no significant new patterns were to appear until 1947 when she was involved with the design of the Princess Elizabeth Perth Wedding Gift set. This set was made up of two decanters, twelve goblets, six sweetmeat dishes, twelve finger bowls, and a large fruit bowl. These are now at Balmoral Castle. Since Monart glass production ended, coincidentally shortly after Isobel’s death in 1961, Moncrieff’s went through various changes, with production of glass finally ending in 1995 when the company was renamed ‘Monax’. In 2000 a separate new company, John Moncrieff Ltd., was set up as a glass trading company, intending to grow to a glass producer again.

The Ysart Family

Salvador Isart was born in Barcelona, Spain, on 30th January 1875. His father was also a glassmaker. But Salvador started his working life in a bakery. Salvador did not enjoy life at the bakery and one day, without telling his parents, he left and took a job at a glass factory. Which company he worked for is unknown, but he started working before he was ten years old.

In 1901 Emile Gallé had formed the “School of Nancy” devoted to Art Nouveau, with various artists, designers and manufacturers. This had a major impact on the development of glass and attracted many glassmakers to migrate to France; Salvador was one of these in 1909. He brought his wife and three sons, and after a spell in Marseilles they settled in Lyons where their fourth son, Antoine, was born. They moved from town to town in France as Salvador worked at different glassworks. Their last move in France was to Choisy-le-Roi on the Seine about six miles from Paris.

Unfortunately, we do not know many details of where Salvador worked in France. We do know that Cristallerie Baccarat was one glassworks and ‘Schneider Fréres et Wolf’ another. When I visited Vincent’s widow, Catherine, in the 1980’s she could recollect very little of this part of her husband’s life. She owned a Legras mushroom lamp which was from that period and very similar to the Monart Cameo examples I had seen, although more sophisticated. It is therefore likely, but not certain, that Salvador worked at Legras & Cie near Paris at some point. At this time, Schneider were specialising as manufacturers of lightbulbs. Certainly, Salvador was working at Schneider when they closed in August 1914, because of the war. After that Salvador found work at other glassworks in the Paris area.

The start of the First World War created a lot of difficulties for British industry as millions were sent to fight, and many to die, in a gruesome war. Agents from British factories scoured Europe to find skilled artisans to work in the UK. The electric light industry was in its adolescence at this time and growing fast. It was not until the early 1920’s that machines were invented to blow lightbulbs and this put increased pressure on the glass industry to find sufficient glassblowers. As the first major war in which electric light was used, such production was also of strategic importance. To help train glassblowers to meet this demand, Salvador Isart was recruited as a Senior Glassblower for the Leith Flint Glass Company (Jenkinson’s) in Edinburgh, Scotland.

During the immigration process, all of the family’s names were anglicised. The Isart became Ysart; their English was not good at this point and the immigration officials probably just interpreted what they heard rather than deliberately changing the names. The full original spelling of each name is given in the Calendar of Ysart Glass.

After a period at Jenkinson’s, Salvador and Paul then joined A & R Cochran Limited, St Rollox Glassworks, Glasgow, where they stayed until the factory closed down. They worked at some other Scottish glassworks until 1922 when they were recruited by Moncrieff’s; Paul started a formal apprenticeship under his father who was hired in the position of Master Glassmaker.

During 1942, Antoine Ysart was accidentally knocked off his bicycle by two youths who dashed out of a side street in Scone near Perth. It was during the blackout and his head hit a kerbstone when he fell; he passed away in hospital three days later.

The Birth of Monart

Salvador had brought some coloured enamels with him from France and he used these to develop the glass now known as Monart. This clearly shows that his move to France from Spain had been to explore new directions and it is likely he only left because of danger from the approaching war. In those five years in France, he had made many moves and this was surely motivated by a desire to soak up the ideas circulating in the French glass industry – or with tongue in cheek, because the French found his temperament too difficult. But seriously, Salvador developed a style that has proven to be quite distinctive. One of the pieces he made was used for a raffle prize for a local church in the Ysarts’ then neighbourhood, the Bridgend area of Perth.

Isobel Moncrieff saw that piece and realised that this type of glassware could be an interesting development for Moncrieff’s. As a woman educated in the arts, she would have been aware of the Nancy movement. Also, her close friend, Mrs Elizabeth Graydon-Stannus, had a keen interest in art glass of the time.

Mrs Graydon-Stannus was an Irish antique glass dealer who had set up various glassworks herself, one in Brittany, France, producing Lalique copies and another, Graydon Glass, in London, making reproductions of antique Irish glass. Her activities attracted a lot of criticism as she was really producing ‘fakes’. In 1925, likely influenced by what Isobel was doing at Moncrieff’s, she had set up Gray-Stan Glass. As Moncrieff’s started to realise full production of Monart glass, the output of Gray-Stan (with a short time lag) echoed it. But Gray-Stan Glass was much more designer driven, and being closer to London, it must have been calculated to dampen remarks being made about her ‘reproduction work’. Later, Nazeing Glass in Essex also followed this trend - they employed some of the glassworkers who had been at Gray-Stan. While this does not prove the case, it does look like the work of Salvador Ysart at Moncrieff’s had a rapid effect on British glass-making.

The design influences on Monart glass were typical for the period. What made it different was the way in which colour was used in the Monart pieces, as well as the iridising of white decoration on the early pieces. This iridising was, reportedly, due to impurities in the gas supply and it must have been a disappointment for the Ysarts when the gas quality was improved. It is presumed that this is the reason, in the later production, that the decoration was all covered in clear glass. However, the 1923 cup in the Perth Museum is not surface decorated. Working after World War II, Paul Ysart was to find ways of repeating this iridising process, and he did make more surface decorated pieces. For collectors of Monart, finding a surface decorated piece is highly desirable. But, quite frankly, many of these were dull and it is possible that this would have made them harder to market at the time. Wenger’s, a supplier of coloured glass to Vasart after the war, advertised an iridising preparation for glass. This ‘might’ have been used at Moncrieff’s for iridising Monart.

The coloured glass produced as MONART GLASS was thus developed by Salvador Ysart in collaboration with Isobel Moncrieff who was largely responsible for the colour designs and pattern shapes. The name is reported by different sources as being derived from the names Moncrieff and Ysart, and alternatively as Moncrieff Art glass. There is no way of getting any proof of the truth in this matter, but the former idea is naturally more attractive to collectors.

Coloured glass powder or granules and canes were rolled (marvering) into clear or coloured blanks and then twisted into whorls, or other pulled decoration, before covering with another layer of clear glass. Sometimes after colouring, striping would be created by using ribbed dip-moulds to concentrate the colour in lines. Bubbles were achieved by sprinkling on crushed charcoal, before the outer layer of glass was added. The charcoal vaporised and formed the bubbles. Many of the earlier pieces were uncased and have a fairly rough surface; some had pieces of millefiori and/or latticinio worked into the surface - a technique that was used extensively later in Vasart, but not with surface decoration. Gold powder or aventurine, and mica flakes giving a silver effect, were often included. Up until the outbreak of World War II, the strong coloured rods had been imported from Schuster & Wilhelmy in East Germany. When these supplies were halted, softer colours from Kügler in West Germany had to be used. The aventurine glass that was included in Monart pieces was supplied by the Gilbert Martin factory in Paris. Paul Ysart would frequently travel to Paris to get the supplies. For the silver decoration mica flakes were used; this was introduced in about 1935. The unusual part of this development is that the supplier was the local Woolworth’s and they only stocked it at Christmas. The only Monart produced between 1939 and 1946 was made by the Ysarts in their lunch breaks or after working hours.

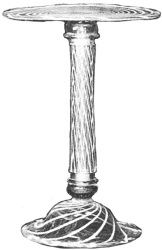

Monart Glass Table 1935 |

In 1935 the Ysarts made a presentation set, including the table illustrated, in clear glass with white stripes. This was intended as a gift from Perth for the Silver Jubilee of King George V. The Perth Selection Committee rejected Moncrieff’s offering, possibly considering it was too fragile. Salvador displayed his Latin temper by destroying almost the entire set, in anger. Only one piece of that remarkable set survived, and it is owned by the Ysart family.

After the war, Paul Ysart stayed at Moncrieff’s and restarted the Monart production, in a much smaller volume. He was helped by an apprentice and later assistant, Chic Young. Paul developed some additional shapes and also recreated surface decorated pieces that are probably indistinguishable from the early examples without analysing the glass. From research by collectors of Monart paperweights, we know that the glass chemistry went through dramatic changes before the 1950’s, see KevH on the Glass Links page. It is likely that these changes were reflected in the glassware, and this would make a good future research project.

During the years of production a great variety of pieces were made, including a handful of fine cut overlay pieces in the style of Legras – although extremely crude by comparison. One such piece now in a Scottish collection, has solid black overlay rising halfway up and it is cut into a ‘trees’ design above. Another is a table lamp base; up to 20 attempts were made to produce a shade for this lamp but with almost every attempt at some point they shattered. The costs of production forced the range to be limited mainly to the familiar whorlly designs in one, two or more colours, and to plainer styled pieces in every possible colour and colour combination. While flower holders in every conceivable shape and size are the most common object, ashtrays, pin trays, plates, coupe & saucer sets, fruit bowls and fruit sets are plentiful. Rarer pieces include table lamps with lit bases and matching shades, ceiling light bowls, lemonade sets, bottles for dressing tables and bathrooms, trays and glasses, as well as some individual non-typical pieces made for friends. Some pieces were made on commission, in specified colours to suit the client’s decoration; in particular, a set of bath salt jars lidded in greys and mauves.

Two catalogues were produced, and images of the first catalogue are available elsewhere on this web site. The Internet Monart Catalogue is based on the second Moncrieff’s catalogue, which has some advantages: we can show the variations in shape, add previously unrecorded sizes, and use colour. But an even greater advantage is that it can be extended to include confirmed Monart shapes that are not in the other catalogues. At the time of writing, some ten such pieces have been added, as well as a catalogue of lighting. Note that adding pieces to this new page is only after very careful scrutiny. Some are special one-offs, made by the Ysarts for their own use, but some must have been production pieces. The latter are possibly special orders from retailers or other customers. The final advantage of the new format is that the colour codes can be illustrated, as labelled pieces are found and verified. Original drawings for a lighting catalogue have been found by Ian Turner, and it will be featured in a forthcoming Glass Association Journal.

For the new, and the seasoned collector, identification can be a headache and a challenge. With several periods of production, not to mention fakes and look-alikes to contend with, there is certainly a lot to be learned. But such challenges surely enhance the satisfactions of collecting. To really learn to identify Ysart Glass, you need to be fooled and make mistakes until you can develop an instinct where you can almost confirm a piece just by its tactile qualities. It is certainly my hope that this web site will be instrumental in limiting the damage caused by those who would produce forgeries. Hopefully, we can also encourage other Scottish glassmakers to develop the Ysart style into new generations - as was achieved by Strathearn and now by individual Scottish glassmakers. Unlike books, where mistakes will still get re-read years after they have been spotted, the new media forms provide an opportunity for collaboration by collectors, in a way that has never been possible before. By publishing in this format, it is not my intention to discourage the writing of books on the subject. Quite the contrary, I would encourage and help anyone who wants to write a book. The details of identifying Ysart Glass are covered on separate pages.

Monart glass has been hidden in obscurity for a long time, despite its close relation to the Nancy School, but then so has most other British glass of this period. There are many reasons for this: identification, low volume production, loss of company records, and glass collectors in the UK were not taking an active interest in local products while French Art glass was still affordable.

The Perth Museum in Scotland contains some interesting Monart glass, as well as a large collection of the best Monart and Vasart paperweights. There is also a cup made in 1923, in orange glass with a few slices of millefiori and a clear glass handle; as well, a red bowl (surface enamel) with embedded latticinio is a beauty. It is well worth the trip to Perth to see this unique collection!

With gratitude to Ian Turner who has done more to unravel the history of Monart glass than anyone else.

References

- Ysartnews 1. This article replaces that one, which had many inaccuracies.

- Ysartnews 2-6.

- Ysart Glass. Ian Turner, Alison Clarke. Frank Andrews, Volo Edition 1990.

- 20th Century Factory Glass, Lesley Jackson, Mitchell Beasley 2000.

- Original research by site contributors.

- Pottery and Glass, October 1947. Article on Moncrieff ‘At the Source’.