A Friendly Talk on Monart Collecting

by Dominic Purdue

Editor: Mary Houston-Lambert

Introduction

The collector of man-made objects who makes no attempt to get to know the lives and times of the people who made them is missing an important and enjoyable aspect of collecting. Some people only collect for investment purposes, but even they will take some interest in getting to know something of the background of their collection. Of course the main reason for collecting is to own beautiful things, ’though collectors know that some desirable items are not particularly beautiful, yet are still collectable for other reasons, usually concerning technique, or rarity.

Nevertheless it remains true that if something of the history of the item is known, an extra layer of interest is added to the thing besides its desirability for aesthetic reasons. That is why it is always disappointing when a piece turns out to have been made by a different person, or at a different time than one believed at the time of purchase. The piece is the same, just as beautiful, but its history is not as it was described or thought, and that is important to most collectors.

Paris in the pre twenties

|

| A Daum tumbler c.1930 similar decoration to Monart but inverted. |

There must have been a tremendously creative atmosphere in Paris at the turn of the last century, especially in the aughts and teens. Gallé had extended the barriers of art in glass along with men like Argy Rousseau and Rene Lalique.

|

| Primavera ceramic jug |

The fashionable Department Store Au Printemps had been first to create an in-house atelier or workshop (the Atelier Primavera) which employed the talents of artists such as Rene Buthaud and Marcel Renard to design interiors and decorative objects to fill them. The new Metro with its Art Nouveau stations and terminals had snaked its way under Paris carrying the bustling city inhabitants, and the art of Monet and Cezanne was still very fashionable among the artistic elite.

Salvador Ysart, a Spanish glassblower, attracted no doubt by these activities and in particular those relating to the art glass industry of the ‘School of Nancy’ in Eastern France, started by; Emille Gallé, Antonin Daum, Louis Majorelle and Eugène Vallin, moved his young family initially to Lyon and found employment as a glassblower working in the new art medium.

Glasgow

In Glasgow, Isobel Dunlop, daughter of a well-known flour merchant, having been educated at a fashionable Glasgow school, was blossoming into an attractive young lady with a very keen interest in art. At that time the work of Charles Rennie Mackintosh was enjoying immense popularity, and he, like his contemporaries at the Atelier Primavera, was integrating external architecture and interior design with sympathetic decorative ornament. In Glasgow, as in Paris, the art and the vitality of the new century were flourishing.

Isobel made the most of her youth, travelling and acquiring the social graces and tastes of the times. On April 9th 1904, in her thirtieth year, she married the Perth industrialist John Moncrieff, in Glasgow.

The Moncrieffs honeymooned in the United States where John kept his mind on business by visiting notable manufacturing processes, including Carnegie’s Detroit Steelworks. Isobel, whose mind was naturally more tuned to things artistic, visited the White House, and is reputed to have ‘bumped into’ the President.

Perth

On their return to Scotland the couple set up house, which they named ‘Rio’, in a fashionable suburb of Perth. Isobel resumed her easygoing lifestyle, entertaining, playing tennis and hosting meetings of the Perth Music and Drama Societies while her husband re-commenced his duties as Managing Director of the Glassworks.

Moncrieff’s in Perth operated three separate factories at that time

- The General Works at St Catherine’s Road making Gauge Glass, Ink and Glue;

- The Shore Works making whiskey bottles for the highland distilleries; and

- Tomey’s where experimentation with a bottle-making machine had yielded promise, resulting in the so-called Monish machine (so named because it was developed jointly by Moncrieff’s and a Mr. McNish) an example of which had been purchased by the Val St. Lambert Glass Works in Belgium.

Artists and Craftsmen

Artistry in glass demands a mastery of the medium that can only be acquired after years of working with the material. Neither the chemistry nor physics of glass are easily mastered. Colours behave differently in glass than on canvas, and different layers of glass cool at different rates according to their characteristics. Differential cooling in glass leads to stress fractures or cracks at the interfaces, while odd and unpredictable colour combinations are often needed to produce desired shades and hues.

|

| Orrefors Ariel: Signed E Ohrstrom. Number is pre war (Ref. Ivo Haanstra). |

It is not unusual therefore to find in the production of art glass that artist and craftsman is not always the same person, in which case collaboration will be required to produce the finished article. The work of Gallé for example, was executed by, among others, Desire Christian and Antoine Burgun, or by Louis Rousseaux, Albert Daigueperce and August Hardy. At Orrefors the master glassblower Gustav Bergkvist would execute the designs of Edvin Ohrstrohm and Vicke Lindstrand produced the Ariel range of glass.

Gallé was an accomplished artist, and though he came from a glassmaking background and was capable of executing masterpieces of his own, he nevertheless surrounded himself with craftsmen who had investigated all the possibilities of the material. It is an interesting point that the young Gallé had met the composer and virtuoso pianist, Franz Liszt, whilst studying at Weimar. Liszt was a brilliant intellectual and a bright artistic light of the time, and clearly influenced the impressionable Gallé. Liszt had pushed his virtuosity to the very limit of human ability, and in so doing had revealed the true capabilities of the piano. His music transcended the then bounds of the instrument; while others called his difficult compositions transcendental studies he called them tone poems. Gallé was later to push his creativity in glass to similar extremes, often combining techniques such as opaque and clear decoration, with metal oxide or silver and gold foil inclusions, wheel cutting and acid engraving, and glass applied like marquetry. Gallé liked these creations to be known as vitrified poems.

Early production

The North British Glassworks of John Moncrieff was unused to the ways of art glass production. There had been some tableware made, in limited production runs, and if colour were used at all it would be as a solid metal, where the whole pot at the furnace would be of that colour.

|

| House of Paul (White) and Salvador (Grey) in Scone, Perthshire. |

When layers of glass are used, each of a different colour or composition, the problem of stress fractures is exacerbated, because cooling contraction proceeds at different rates in the different layers. This problem was to dog art glass production at Moncrieff’s. In all likelihood, pieces were passed and sold as perfect, containing small annealing cracks, as some of these were (and are) very difficult to detect.

During the latter part of 1923 and in early 1924 Salvador Ysart worked with Isobel Moncrieff, as Christian and Burgun had worked with Gallé. Classical shapes from ancient Greece were employed, as well as more contemporary styles. Different metals were tried and abandoned and a variety of more modern shapes included or discarded.

The role of Isobel Moncrieff

Isobel Moncrieff was a petite redheaded woman with a vital sense of life and fun. She was a very popular figure around the town and the glassworks. The workforce affectionately knew her as Lady Moncrieff, and the local constabulary would often have to sheepishly ask her to move her car because she was in the habit of leaving it abandoned rather than parked. Having become interested in the coloured glassware being made by Salvador in his lunchbreaks, she encouraged him to make vases of different shapes and colours.

Isobel became artist to Salvador’s craftsman. She it was who designed the colour schemes that were to make the glass so popular then and now. She would bring printed fabrics from home and abroad and challenge Salvador to copy them in glass. She drew heavily, just as Gallé had done, on the colours of nature all around. The Monart vase is difficult to find whose colours cannot be seen at some time of year in the Perthshire countryside, in the waters of the Tay, or in the skies of Eastern Scotland. The colours and patterns of paisley shawls and tweed scarves were also transfused into the glass of vases and bowls.

Isobel sketched in colour and to scale every piece of glass that was to go into production. Listed on the sheet with the life-size drawing were details of the colour mix in the form of a code. This same code appeared on the pre-war labels applied on the base of the pieces over the large pontil mark, along with the size and shape codes.

Two large volumes of these drawings encompassed the whole range. If a customer wanted to replace a piece he had damaged or broken, he would simply write to Moncrieff’s with the code details. The appropriate volume of drawings would be consulted, and calipers run over the drawing at each point to get the dimensions. Then, using the colour and shape code, the piece could be reproduced.

The new range of glassware was named Monart. This name used the first three letters of the Moncrieff name and the last three of the Ysart name, while at once conveying the fact that each item was indeed a work of art. There remains some doubt as to the authenticity of that fact but there was a antecedent for such a naming scheme in the Monish bottle machine. (Moncrieff - McNish c.1928)

These beautifully coloured items emerged from corners of the hot dusty and ill-lit factory, mostly in the 1920’s and thirties, and found their way, sometimes via the catalogues of Liberty of London (where they were displayed with Argy Rousseau and Gallé), to the homes of the middle classes.

Colour was introduced into the glass in the form of opaque mottles or speckles. Coloured glass arrived at the factory in sausage shaped rods rather like black puddings. These would be broken up using a metal pestle and mortar. The resultant crush would be sieved through three sizes of mesh to give a course, medium and fine grain. These would pass under a powerful magnet to take out any metal from the crushing process, and would be stored in containers labelled with the colour and mesh size. Failure to remove even a small fragment of metal would result in a dark mark in the finished glass.

During early production it was common to marver (or work on a flat steel bed) the coloured enamels onto the clear or milky core glass molten ball, blow and work the shape, and anneal as is with no outer clear glass case.

Sometimes a lustre effect would be added to the coloured surface by exposing the molten glass to an unlit gas fume. Sulphurous impurities in the gas would react with components of the glass to give a lustre effect not unlike that seen on carnival glass. The local Corporation Gas Works during 1925, oblivious to the requirement of the Glass Works, installed a filter system to remove the sulphur, and much of a whole week’s glass production suffered a no-lustre finish. Although attempts to restore the missing impurity to the gas at the furnace mouth were reasonably successful, it is unlikely that much lustrous surface ware was produced after about 1926.

The War Years

|

| The Moncrieff factory at St Catherines Road, Perth being demolished. |

In 1933 John Moncrieff stepped down as Managing Director and Isobel’s interest in the glassworks began to fade. Her influence continued however, and her legacy was the hand drawn and coloured catalogues, which were in use as long as Monart production continued. These catalogues are thought to have been destroyed when Monart production finally ceased. If they were to be discovered intact, they would indeed constitute a treasure. [2005 Ian Turner has these.]

All Monart production ceased with the outbreak of the Second World War. The War Office needed to divert production away from the artistic and frivolous, to more serious work. The Perthshire Advertiser Annual Review for the year 1939 reported the suspension of Monart production thus:

“Gauge glass and laboratory and engineering glass remain in fairly steady demand but, naturally, with the advent of the war, Monart Glass must necessarily suffer a temporary ‘black-out’ as in the case of most articles of a semi luxury nature.”

Vasart

After the war, the Ysarts, and Salvador in particular, wanted to return as quickly as possible to producing Monart. But the post-war period was a frugal time. Rationing was still in force, and the country needed to repay its war debts by exporting goods required for rebuilding Europe. These did not include ornamental glassware.

As early as 1946, Salvador and two of his remaining sons (Vincent and Augustine - Antoine had been killed in a wartime accident) set up their own glassworks in derelict sheds at Shore Road in Perth. Their new firm was originally called Ysart Brothers, but later changed to Vasart Glass in 1956. (Vincent Augustine and Salvador YsArt). They worked quickly and for long hours, and in a month they had begun production. From the start they called the glass Vasart.

Initially their glass was very similar to Monart, with deep colours and liberal amounts of Aventurine (the goldstone that had virtually characterised Monart ware). Moncrieff’s, as one can imagine, were less than delighted at these events and the story goes that they contacted their colour suppliers and warned them to cease supply to the Ysart Brothers, or risk losing the Monart contract. Consequently, within a relatively short time the Vasart colours began to run out. The Ysarts were familiar with glass chemistry and could purchase the raw materials needed to make colours; but the results were less than satisfactory. Washed out, thin pastel shades resulted, and these less than vibrant colours characterise much of the Vasart glass we see today. At some point, Vasart used colours supplied by the English firm Wengers.

Post war Monart

In the meantime, at Moncrieff’s, Paul Ysart resumed production of Monart in late 1946, with the making of one of the City of Perth’s wedding gifts to the Princess Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh. He could not do so on his own of course, and he recruited a man named Johnny Jones from Edinburgh and Leith Flint Glass Works. The glass industry is fairly parochial and Paul had kept in touch with workers in Edinburgh, and in fact bought lampwork snakes and dragonflies from a glassmaker there for his paperweights. Johnny Jones remembers well travelling up from Edinburgh, and staying at Paul Ysart’s house in Perth overnight, while he looked over the job. “The bath was full of paperweights”, he recalls “and the house was awash with beautiful vases and decorative glassware.”

Around six or seven sets of the ‘Wedding Gift’ tableware were made, and the best pieces were selected to make up a set for presentation to the Royal Household.

Post war Monart production, at least during Johnny Jones’ days, only amounted to about a couple of dozen pieces per day at most. Paul was becoming more and more interested in paperweight making, and would recruit Jones, or more often Chic Young, to help in the lunch break. “I preferred to eat my pieces (sandwiches) most of the time” explained Johnny Jones.

The Ysarts’ privileges

After 1926 much more of the production was finished in a casing of clear glass, which served to lock the colours in a gloss finish, and finishing the uncased colour with lustre became a less and less used technique.

During these early years, Paul and sometimes Salvador as well could be called back to normal production, that is working on laboratory or industrial glass, at a moment’s notice as needs demanded.

As time passed, Salvador’s other sons Vincent, Augustine and Antoine came into the profession and were apprenticed in turn to their father. Each would of course learn the rudiments of the profession on the factory’s main lines, and would later return to them with the rest of the family when required.

Prior to World War II, the Monart shop was off-limits to anyone except the Ysarts and one or two other people. Here the colours were stored, the catalogues were kept, and all the secrets of production were jealously guarded.

It is not difficult to imagine the privileges afforded to the Ysarts by their position in the art glass shop. Here were colours, textures and shapes that featured in the Liberty Christmas Catalogues alongside Argy Rousseau and Gallé. The glass had taken the market by storm. Never cheap, the vases, bowls, vessels and lamps adorned Watson’s, the best glass emporium in Perth, and were being exported weekly to London and beyond. The Ysart boys too, with their Latin looks and charm to match, were seen as a threat by their Perthshire peers in the battle for the attention of the available young ladies.

Paul Ysart was particularly disliked. He was a hard taskmaster at work; he did not get on well with his fellows and because of his secrecy he offered little in the way of imparting his skills to others at Moncrieff’s. He had his father’s temper, and in the post-war years when he no longer spoke to his father, he had little time for anyone else who did. On one occasion (post-war) the glassblower helping Paul at the time (you can do nothing on your own in a glassworks) had a coloured sugar bowl and matching milk jug in the Lehr, which he had made for his landlady. When Paul returned from his lunch and saw them, he put the punty iron through them both. “You’ll make nothing here,” he told the glassblower.

Braso’s Baskets

|

| Braso basket |

|

| Braso at Work |

Colour for the making of friggers was expressly forbidden to all except another Spanish glassblower by the name of Jesus (pronounced Hey Soo) Braso. Salvador had recruited Braso for Moncrieff’s on a trip to Spain. Braso was a short stocky man with a huge barrel chest. He could blow the biggest desiccators for Moncrieff’s and had the enormous strength needed to hold the weight of the hot glass, whilst swinging it about his head. His hands were so heavily calloused from handling the hot irons that he could hardly close them. His party trick, for the benefit of the amazed apprentices, was to pick up with one hand the boiling Billy can he used to make his tea and rest it in the palm of the other, while the smoke billowed up from his skin.

Braso’s speciality in the frigger department was his baskets. The body would be in a muted colour with a complimentary coloured trail of thick cane spiralling round the outside of the mouth of the basket. The handle and base would be of clear crystal, with pinched decoration. In contrast to the Ysarts, Braso was well liked by his fellow workers.

The declining years

Salvador died in 1955 and Augustine in 1956. Only Vincent remained at Ysart Brothers Glass. By 1960 Vincent had hired Stuart Drysdale to help manage the company (alongside George Dunlop - already a director). Isobel Moncrieff died in 1961. In 1963 the company (now called Vasart Glass Limited), was commissioned by the administration of Sir Alec Douglas-Home the then Prime Minister, to manufacture and supply new light shades for the Downing Street offices. Jesus Braso, the barrel chested Spaniard was tempted out of retirement to help make these globes, as he alone had the necessary skill and strength to complete the task.

In 1963 Paul Ysart joined Caithness Glass as a training officer. Vasart became Strathearn in late 1964, and opened a new factory in Crieff in early 1965. During that year Vincent Ysart left Strathearn to work as a clerk at an insurance company where he became the victim of an unfortunate accident. He died later in the same year.In 1975 Paul Ysart made paperweights and possibly other items at Harland. Paul died on December 18th 1991.

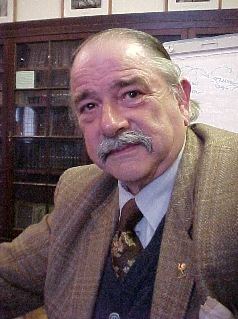

John Jones pictured while visiting the Reserve Collection at the Perth Museum.

John Jones pictured while visiting the Reserve Collection at the Perth Museum.Mr. Jones began working at Moncrieff’s with Paul Ysart in 1946 and together they made the Wedding Gift Set in that year. (Ref. Perthshire Advertiser Annual Review 1946 - AK Bell Public Library Perth)

Mr Jones began collecting Monart Glass years after leaving Moncrieff’s. He sold his personal collection in 1974, completely monopolising the saleroom for three days. His collection comprised sixty tea chests full of Monart pieces.

His experience with Monart glass, both as collector and first-hand as a glassblower working with the glass, is truly unique. He knew the Ysarts well and although he never worked with Salvador, Augustine or Vincent, he would visit them at the Shore Works (a fact that did not meet with the approval of Paul who had fallen out with his father).

He recalls one instance when he bought a Tulip Lamp from Salvador for £1 during his lunch break, and got into trouble with Paul on his return to work for having spoken with the “auld ingin” (Old onion as Salvador was affectionately known).

Collecting Monart

|

| Last chunk of glass: From a furnace at Moncrieff given by the demolition foreman before the building was completely demolished. |

Monart glass is still readily available to the collector. Prices vary of course, and can be cyclical in that they climb and remain high for a while, then drop to reasonable levels again.

It is tempting to travel to Perth and its surrounds to look for Monart and Vasart ware. But let the buyer beware, for this has long been the centre for very expensive examples, and it remains the source of many fakes.

It is possible still to buy examples at fairs, car boot sales and junk shops for very little money. I purchased an excellent vase for £5 recently, and a Vasart lamp for £10.

One way to build up a good and inexpensive collection is to buy examples with annealing cracks. These remain relatively cheap, and after all were commonplace during production runs; they are not the result of post-production abuse or accident. These are very display-able and enable the collector to amass a big collection cheaply. Monart glass is best seen in the company of other examples, because the vivid colours complement each other well.

Such a collection is also a valuable etude in that the collector can study manufacturing and decorating techniques, as well as base pontil finishing.

At first, the collector avidly adds any example to his collection, but as the collection grows so the collector matures and concentrates on certain aspects only. These may be large pieces only, for example, or unusual shapes; or the collector may concentrate on having one example of each catalogue shape.

The biggest threat to the collector is undoubtedly fakes. As I mentioned earlier on, the history of the piece is of great importance to the collector. It is a huge disappointment to discover that the piece you have purchased in good faith may have been made only last week.

Perth, at the moment, is a minefield for the collector, offering both genuine and fake pieces. There are capable people in the area with the know-how and opportunity to produce the fakes. Fortunately there are ways to detect them - not foolproof, but of sufficient use to be very helpful in sorting out the real thing.

The table on the fakes page has been compiled with the help of the book “Ysart Glass”, Frank Andrews, and personal experience of buying fakes inadvertently.

©2002 Dominic Purdue & ©2005 Ysartglass.com. May 2002

References

- Ysart Glass. Turner, Andrews, Clarke. Volo Edition 1990, ISBN 0 9514465 1 7

- Ysartnews - Newsletters of the Monart and Vasart Collectors Club, 1986-93. Editor. Frank Andrews

- The Glass Club Bulletin. - National American Glass Club, No.118 December 1976

- Frank Andrews - Personal communications 1999-2002

- Ysart Glass Website - http://www.ysartglass.com/

- Sandy Forsyth - Personal communications Gallery One Perth

- Press Archives - The AK Bell Public Library Perth

- The Museum and Art Gallery Perth

- John Jones - Glassblower and assistant to Paul Ysart 1946-49. Personal communications 1999-2002

- Hildegarde Berwick - Former curator Perth Museum and Art Gallery. Personal communication 1999